BY CHERESE COBB, FREELANCER

Local animal shelters have been transformed by adoption booms and plummeting pet populations. But be sure of this: they’ll never run out of animals in need.

Few shelters are empty. The Wisconsin Humane Society (WHS) in Milwaukee, Wis., has 250 adoptable animals, though more than 80 percent are in foster homes.

The heartening news is that Wisconsinites have stepped up by the thousands to adopt, foster and make masks as social distancing combined with skeleton staffing has closed shelters to the public and sent adoptions online.

“On March 15, we asked for the public’s help to clear our shelters. Three hundred and nineteen animals went to foster or adoptive homes that week,” says Angela Speed, vice president of communications at WHS. “The community support was awesome and humbling—we couldn’t be more grateful.”

The WHS’s Milwaukee and Green Bay campuses are open for adoptions by appointment. “We’re doing foster-facilitated adoptions and limiting our intake to emergencies. But we recognize that transport intake can be as much of an emergency as a surrender from a family who’s losing their home or an injured stray,” Speed says. “When an overcrowded shelter must choose between transporting animals to us or euthanizing for space, that’s an emergency.”

On March 13, the WHS paused all out-of-state transports. They make social distancing difficult for staff and volunteers. “Transported animals need physical space as well as many interactions with our limited staff,” she says, “further eroding social distancing and limiting our ability to prepare for whatever challenges arise next.”

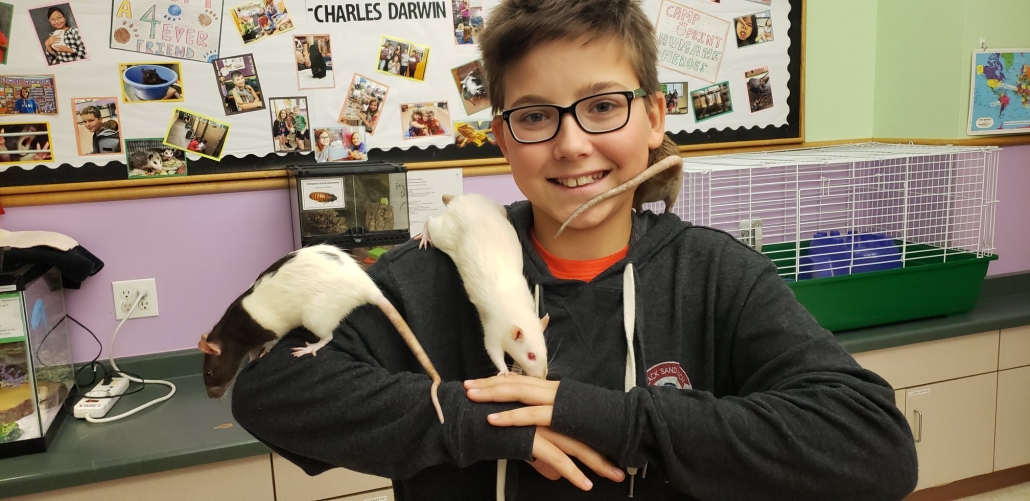

Catie Koss runs Diamond Dog Rescue LLC (DDR), in Madison, Wis. The foster-based rescue doesn’t have an actual building, but it’s found homes for 1,200 dogs. “We still pull from other states as where we pull from is very rural and hasn’t seen many, if any, cases,” Koss says. “If we stopped doing intakes right now, 54 animals would have likely been killed. So we operate under the assumption that we’re all carrying the virus without knowing it.”

“We haven’t done our normal intakes where we bring the dogs to a location, process paperwork and then fosters pick them up,” Koss says. “Instead, I’ve made the drive to each foster’s home.” Because she’s a home healthcare professional, Koss is cautious while she’s on the road. She wears a mask for pick ups or drop offs, and fosters leave out sanitized crates. Once they bring their dogs inside, they bathe them, change clothes and sanitize the crate again. “I’ve created a mobile bin in the back of my truck to sort paperwork and keep everything as clean and sanitary as possible,” she says.

“We’ve always done most of our home visits virtually because many of our adopters travel for several hours. You can see anything you need to see around the home and still get a great feel for the people you’re speaking with.” DDR’s adoptions take place outside with no human-to-human contact. When animals change hands, they’re given a bath in case their fur carries coronavirus. The organization also sends adoption paperwork electronically. And adopters can submit payment through PayPal or the rescue’s website.

Dane County Humane Society (DCHS) only has one adoptable animal: a 20-year-old chestnut-colored gelding named Big Boy. It has suspended its volunteer program. “That’s an extra 900 people that would have been in the shelter every week,” says Amy Good, director of development and marketing at DCHS. “Normally, we have nearly a hundred employees on a given shift.” Its reduced crew of 20 is stretched thin because of the spring wildlife baby boom.

Good currently works from home. “We’ve had some interruptions on Zoom because my dogs decided to play fight, or of course, my cat walked across the keyboard,” she says. Though she’s not working at the shelter every day, she’s surrounded by animals that have been helped by it. “That’s a great way to keep grounded,” she says.

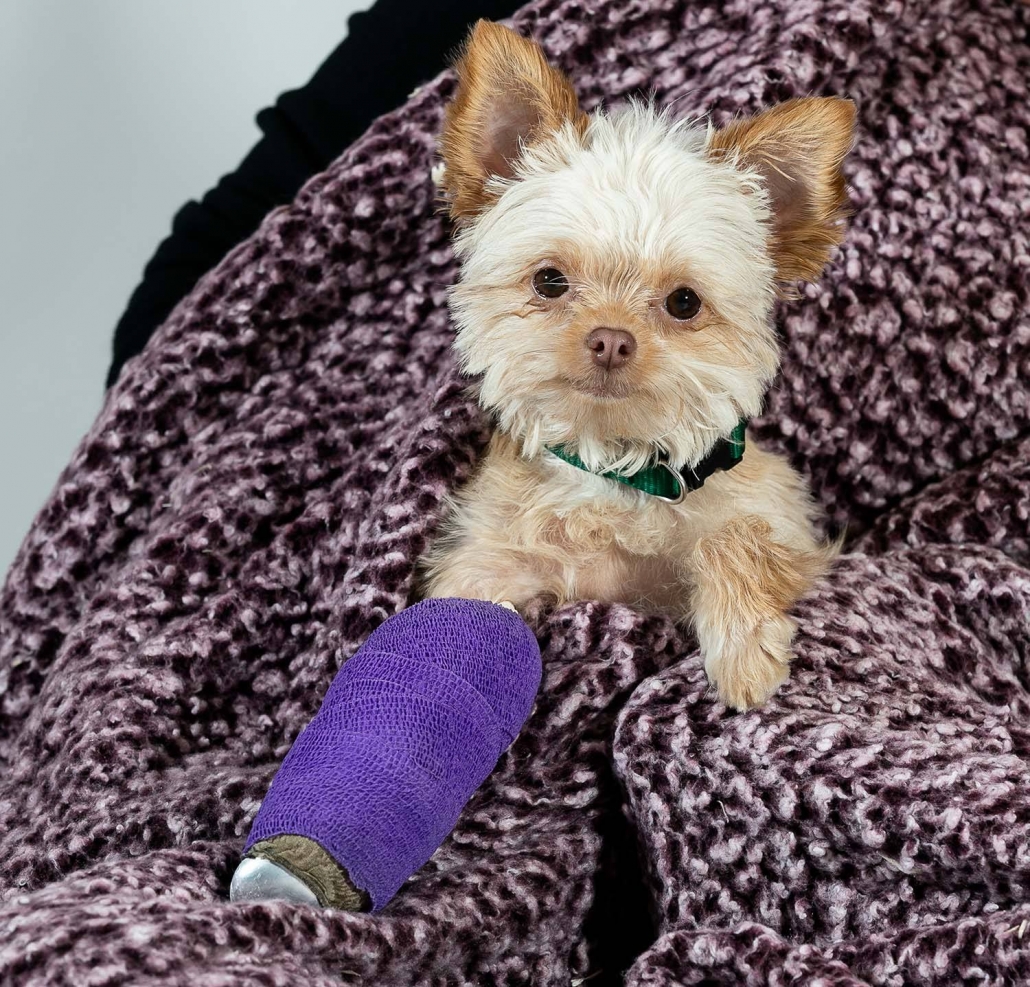

Unfortunately, DCHS is starting to see animals come in from people who have been hospitalized with COVID-19. “We’ve had one person do an outright surrender, but we’re holding on to the other animals. One was already returned,” she says. “If you’re sick and you need this particular program, normally we’d ask for fees. But our goal is to reunite pets with their families, and we don’t want money to be a barrier to that.”

Good urges community members to have a disaster preparedness plan for their pets. “If your animal never needs to come to our shelter and can stay with a family member or friend, that’s the ideal situation,” she says. You should keep your animal’s vaccine record and medicine list on hand. Stock up extra food and supplies that can last at least two weeks. And your pet should have proper identification such as a collar with an ID tag and a phone number.

As the country reopens bit by bit, there’s a great fear that owner surrenders will skyrocket. But returning to work means people who’ve lost their jobs during lockdown can pay for pet food and supplies.

Because people are sheltering in place, they’re going to deeply bond with their pets. “Some people who reached out to us to adopt are working from home, but they thought this was the perfect time to transition a new animal in,” Good says. “If animals do come back to us, we’ll know more about them when we adopt them out to their next families, but for the most part, these adoptions will stick.”